A virtual innovation bootcamp to remotely connect… Leave a comment

This was a four-week, immersive virtual innovation bootcamp that incorporated small-group-based experiential learning focused on healthcare innovation and entrepreneurship using online videos, virtual office hours and design reviews, along with a capstone pitch competition. It was developed for any undergraduate or graduate student, but primarily focused on healthcare professional students and engineering, business and other arts and sciences students interested in healthcare.

The bootcamp aimed to improve understanding in five core-knowledge-focused objectives: (i) performing market research; (ii) developing a solution/prototype for a specific problem; (iii) business plan development; (iv) pitching/presenting an idea; and (v) working on a multidisciplinary team through the design and entrepreneurship process. Additionally, there were several objectives designed to impart interprofessional training through innovation and entrepreneurial experiences: (i) foster relationships that demonstrate how to collaborate on a multidisciplinary team to promote health; (ii) impart experience with healthcare technology, innovation and entrepreneurship; (iii) enable a sense of contribution to healthcare during the pandemic; (iv) provide a better opportunity for sustained learning compared to the weekend ‘hackathons’ common across university environments; (v) provide opportunities to work with students from other disciplines, universities or regions of the world; (vi) achieve participation from women and minority students that is representative of our healthcare communities; and (vii) advance innovations designed to improve health in the pandemic.

Preparation

We hosted the bootcamp between 11 May and 5 June 2020. Given the rapid acceleration of the pandemic, we spent four weeks before the start of the bootcamp developing the curriculum and collaborative platform. Eight Sling Health volunteers organized and ran the program.

Recruitment strategy

Sling Health leveraged its nationwide network of innovators while engaging in outreach to related organizations. Promotional materials were sent to all chapters to use in further advertising the event to their respective institutions. Through national and chapter partnerships (for example, with the American Medical Association, national hackathon organizations and professional affinity groups), the bootcamp received additional exposure to students with aligned interests. Advisors were contacted at universities across the country to disperse information. The bootcamp value proposition drove recruitment: connection to peers with similar motivation, access to diverse mentors, a cogent learning structure and abundant resources to actualize the COVID-19 solutions developed. Prospective participants, who could join either individually or with an established team, completed an online application for consideration (Supplementary Note, Appendix A). We also recruited experts and professionals to serve as mentors for teams by distributing a sign-up form to chapter mentors and community partners (Supplementary Note, Appendix B). Mentors were chosen based on their field of expertise and availability. Ultimately, 26 experts actively served as mentors throughout the four weeks—a mentor-to-student ratio of roughly 1:3.

Communication tools

Web-based virtual collaboration and video conference tools were used for the bootcamp (for example, Slack, Google Sheets and Zoom). Virtual workspaces on Slack were created for team communication, announcements, deliverable deadlines and mentor collaboration. Participants were given online access to a high-level view of the program, submission links with due dates for deliverables, direct links to educational resources (for example, patent application support) and sign-up sheets for design reviews and mentor chats (Supplementary Note, Appendix C; names removed for privacy).

Team formation

Team formation began three days before the bootcamp started. A Slack channel dedicated to the formation of teams offered a space to post introductions, search for teams to join, or seek talent to build existing teams. Participants were encouraged to be proactive about seeking teams where their skills could be well used, as well as to include students from various disciplines (healthcare, engineering, business, etc.) and institutions. Ultimately, students were given complete autonomy in forming teams.

Structure

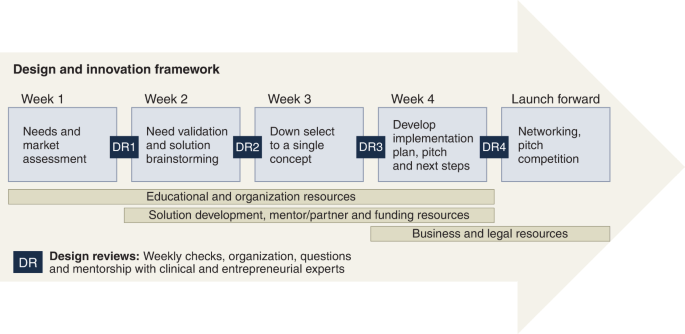

The bootcamp was inspired by Sling Health’s eight-month program that uses biodesign and lean-startup principles and is designed to emphasize rapid development, engagement and access to feedback14,15. The bootcamp started with an onboarding meeting at which participants were introduced to the communication tools, resources and program timeline (Fig. 1). The educational curriculum focused on five core objectives (performing market research, developing a solution/prototype, constructing a business plan, pitching/presenting an idea and working on a multidisciplinary team) and progressed in a weekly fashion (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Design and innovation framework of virtual innovation bootcamp.

Flow chart depicting the different stages of team progression during the Virtual Innovation Bootcamp from a curricular and resource standpoint. Dark gray boxes define weekly goals and objectives. Illustration provided by A. Dicks and A. Robinson in association with InPrint at Washington University in St. Louis.

The Sling Health executive team guided students through the program. At the beginning of each week, an executive member hosted a program-wide check-in to outline goals and events. Additionally, teams were paired with a Sling Health liaison to streamline communication, ensure team progression through bootcamp milestones and discuss relevant resources.

Finally, weekly design reviews (DR) were held, with a panel of two to four mentors and participating teams concluding each week’s programming. The teams received feedback and guidance based on the week’s milestones (Fig. 1). Each DR was 30 minutes in length, with 15 minutes reserved for presentation and 15 minutes for mentor feedback. These DR sessions were organized within larger 90-minute blocks, in which mentors attended three consecutive sessions. Requiring teams to attend the full 90-minute blocks meant that teams could learn from their peers, contributed to a sense of community within the program and helped build inter-team relationships that could extend beyond the confines of the bootcamp. Recommended deliverables for each DR were given to students in the orientation guide (Supplementary Note, Appendix D).

Resources

An educational orientation guide describing the overall goals, with details about program milestones, served as the backbone of this learning experience (Supplementary Note, Appendix D). In partnership with the Entrepreneurship for Biomedicine program funded by the US National Institutes of Health16, instructional videos were curated to explain innovation and entrepreneurship concepts to support students without a background in the field. Additional lectures from experts in healthcare, venture capital and startup accelerators, and entrepreneurship were curated from YouTube and prepared students for their next steps after the bootcamp (Supplementary Note, Appendix C). The bootcamp also provided in-kind and financial services to support the projects. Teams could apply for support for up to $500 in prototyping expenses per week, awarded based on merit and development needs determined using an online application (Supplementary Note, Appendix E). Additionally, over $2,000 in prize money was awarded to the top three teams to support development after the bootcamp. In partnership with a cooperative that connects patients with healthcare innovators, teams could conduct patient surveys to gain first-hand insights on their problem of focus. Partnerships with a law firm and a startup company that facilitated automated prior-art searches provided teams free provisional patent submissions and understanding of the patent landscape, respectively.

Program evaluation

At the program’s conclusion, we conducted a cross-sectional program evaluation and survey of all matriculated participants. We collected demographic information, participant academic background data, education metrics, participant satisfaction and opinion data, and team achievement and outcome data (Supplementary Note, Appendix F). Participants’ pre- and post-program self-proficiency ratings for educational objectives were collected on a five-point scale (1 = unfamiliar, 5 = can lead a team on this task) and analyzed using paired, two-tailed t-tests in Microsoft Excel. A P value of <0.01 was considered significant. This research was deemed a programmatic evaluation by the Institutional Review Board at Harvard University and did not require approval.